SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[Part 1] When Taal Volcano erupted for 6 months](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/612F469A6EA84F6BAE882D2B94A4B421/img/D622BAC5417442B28243405B8BC8286F/taal-1754-eruption-illustration-01.jpg)

TALISAY, Philippines (UPDATED) – Few remember that 264 years ago, Taal Volcano experienced a devastating eruption lasting almost 7 months.

The 1754 eruption is, to date, Taal Volcano’s biggest eruption. Beginning on May 15, 1754 and ending on December 5 that year, it buried 4 Batangas towns under ash, volcanic rocks, and water.

It brought about days of ink-black darkness and changed the topography and characteristics of the Taal Volcano and Lake system.

This May, Rappler commemorates the anniversary of the start of the eruption with a two-part special. The first recalls the eruption and how it changed the course of history. The second explores the possibility of such an eruption happening today and what measures have been taken to prepare for it.

***

‘On May 15, 1754, at about 9 or 10 o’clock in the evening, the volcano quite unexpectedly commenced to roar and emit sky-high, formidable flames intermixed with glowing rocks which, falling back upon the island and rolling down the slopes of the mountain, created the impression of a large river of fire.’

Thus begins the horrific account of Father Buencochillo, an Augustinian priest who had witnessed the 1754 eruption from the town of Taal.

His writings, which sound straight out of an apocalyptic film script, were preserved in a 1911 book by Jesuit Miguel Saderra Maso.

In 1754, Taal town was on the shores of Taal Lake. It was one of the 4 ancient Batangas towns that had been buried by the months-long eruption.

The priest recalled how Taal Volcano continued in this state for 19 days, until June 2.

On that day, the flaming rocks and debris expelled by the volcano “made the entire island appear to be on fire.” At the time, the debris had still not reached the communities in the mainland.

From then until September 25, a period of 116 days, the volcano belched out fire and mud of such darkness that “the best ink does not cause so black a stain.”

The black smoke streaming upwards from the main crater was also topped by a “huge tempest cloud” where thunderstorms would form. Forks of lightning would then cut through the smoke, said Buencochillo.

On September 26, the residents of Taal had to leave their homes because their roofs, groaning under the weight of ashes and stones, threatened to collapse.

The depth of ashes and stones exceeded 45 centimeters (1.5 feet), said the foreign priest. It left no tree or plant standing. That day, Taal Volcano appeared to calm down but not enough to comfort the people on the mainland.

On the night of November 1, the volcano once again woke up, even angrier than before.

It disgorged more rocks, sand, mud, and fire. Fifteen days later, it vomited gigantic boulders that rolled down the slopes of the island and fell into the lake.

Buencochillo felt the ground beneath him sway. Houses in the town fell to the ground.

It was on November 28 when Taaleños escaped from their town. That night, the volcano unleashed its largest explosion. The amount of debris it expelled in a few hours, said Buencochillo, exceeded the amount it expelled over the previous months.

The entire Volcano Island was covered in glowing rocks and ashes. Violent earthquakes shook the ground and caused the lake to heave. The chaos below was reflected in the skies above – crisscrossed with lighting and reverberating with thunder.

Finally, the cloud of debris began to extend near the mainland, carried by the wind. Stones began to fall close to the shore. Lake waters began to claim the houses by the beach.

Fr Buencochillo wrote:

‘We left the town, fleeing this living picture of Sodom, with incessant fear lest the raging waters of the lake overtake us, which were at the moment invading the main part of the town, sweeping away everything they encountered.’

The aftermath

Buencochillo and many Taaleños had taken refuge in Caysasay, which today is a village in present-day Taal town.

A few days later, during the first week of December, the volcano calmed down. The priest returned to survey the damage.

Nothing was left of the old Taal, save for the walls of the church and convent. All other structures were buried beneath a layer of stones, mud and ashes more than 7 feet deep.

Nearby Pansipit River – which connects Taal Lake to Balayan Bay and the West Philippine Sea – was partially buried. River and lake waters displaced by the ejected debris had submerged, not only Taal, but also old Lipa, Tanauan, and Sala.

The eruption, and others that followed it, led the transfer of the towns to other sites. Today, Taal town is farther from the southern shores of Taal Lake and closer to Balayan Bay.

The site of old Taal is now occupied by a new town, San Nicolas.

But remnants of the past still exist.

Near the San Nicolas public market and a few feet from the lakeshore lies a fern and moss-covered shell of stone walls. These are the very same walls that Fr Buencochillo found still standing, half-buried in ash – the walls of the old Taal cathedral.

Volcanologists today are still finding ash deposits from the 1754 eruption under layers of more recently-expelled ash.

Locals of San Nicolas still tell stories of eerie building-like formations under the water.

Melvin Holgado, a resident of the town, told Rappler, “There are many fishermen who say, when they dive over there, they can see a building similar to a city hall. It has doors, windows. They sometimes turn back because they get scared.”

Another San Nicolas local, Frankie Matienzo, shared, “Before, some people would see a cross from the sunken cemetery at around this time, summer season. They don’t see it anymore. I last saw that cross when I was in elementary.”

A present-day perspective

Buencochillo’s thrilling account of the eruption matches descriptions of major eruptions studied by scientists.

Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) Director Renato Solidum Jr said the 1754 eruption is a classic Plinian eruption defined as an “eruption of great violence characterized by voluminous explosive ejections of pumice and ash flows.”

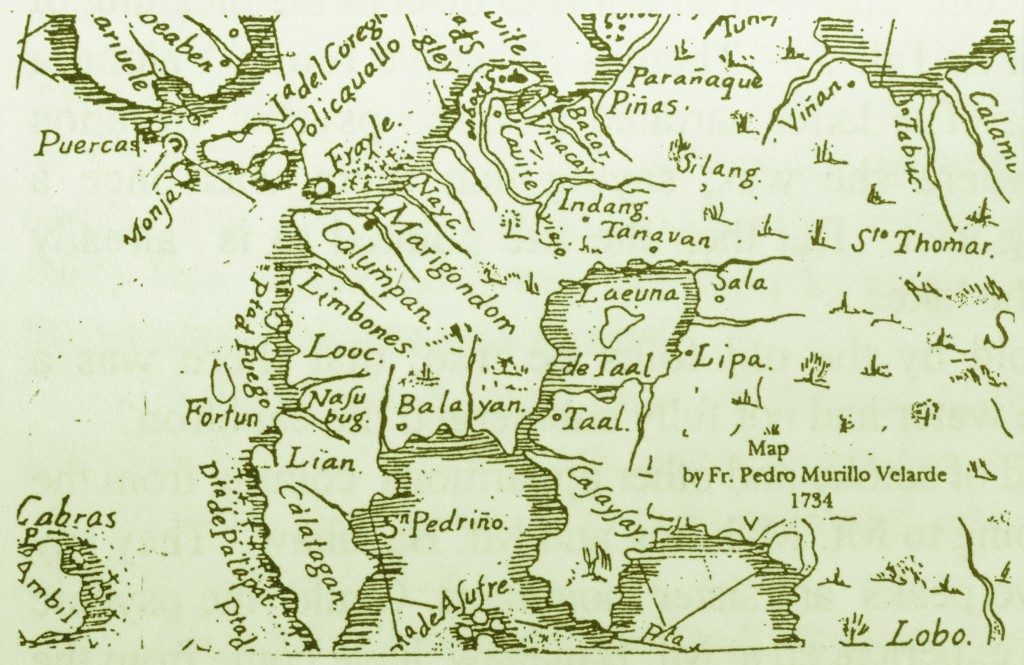

But what makes the 1754 eruption unique is the topography of Taal Volcano. Unlike most regular volcanoes with a small crater on a high elevation, Taal’s main crater is very wide, very low, and surrounded by water. (MAP: Active volcanoes in the Philippines)

The 1754 eruption thus produced a base surge – a horizontal flow of hot gases, ashes, and rocks.

Unconfined by a small crater, this flow, called a “pyroclastic flow”, spreads out horizontally traveling 80 kilometers an hour even across water, said Solidum.

“That base surge can cross Taal Lake and reach the shoreline in the surrounding mainland and, in fact, during the 1754 eruption, the base surge actually moved upslope towards Tagaytay ridge,” he told Rappler.

Base surge is the most dangerous hazard during a 1754-like eruption, said Solidum.

“It can bury a person or any object. It can erode it, it can blast it away. The object can be burned. If it’s people then sometimes people cannot breathe because the pyroclastic flow, as it would move, will ingest air in front of it.”

The heaving lake waters described by Fr Buencochillo could also have been the phenomenon now referred to as “seiches” or lake water oscillation by scientists.

Solidum likened a seiche to a volcanic tsunami.

Because Taal Volcano is in the middle of a lake, any vibration or explosion it creates can move water as high as 10 feet.

Can you imagine a repeat of the 1754 eruption in this day and age? Would communities be affected the same way or would the damage be greater? What have we done to prepare for it?

Find out in the second part of this series. – Rappler.com

To be continued

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.