SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

CEBU, Philippines – Voices break out in laughter in a small corner of San Francisco town in the Camotes Islands.

In a large shed, some 50 people sit on monobloc chairs: mothers with babies on their laps, kids eating candy, old men peering from underneath worn-out caps.

They comprise the purok of Paypay, a geographical unit smaller than a barangay which has earned San Francisco town international recognition.

The purok members listen to their purok officers, mostly women, and two coordinators, both men, explain a new ordinance requiring homeowners to keep their dogs inside their homes during the night to prevent road accidents.

Marcos, a purok coordinator, takes the stage to warn the purok about the coming El Niño, advising them to plant sweet potato instead of crops like rice and corn which need a lot of water.

The purok members listen aptly but the meeting, by no means serious, is again interrupted by good-natured laughter and teasing.

Such a scene plays out in the town almost daily because “San Fran,” as locals fondly call it, is home to 120 active puroks.

In 2011, the town won the United Nations Sasakawa Award for Disaster Risk Reduction because of how it made use of the purok system to save lives during calamities. (READ: 6 ways climate change will affect PH cities)

True enough, after Super Typhoon Yolanda laid waste to much of Eastern Visayas in November 2013, the town reported zero casualty in a time when its bigger neighbors – cities and larger towns in Leyte and Samar – were counting death tolls by the thousands.

The purok

The concept of a purok is nothing new. It was introduced in the 1950s to bring education to the masses. But community organization soon fell on the lap of barangays or villages which had the power to impose taxes, service fees and fines and thus generate income. Many puroks all over the country are no longer active because they have no such source of funds.

| Classification: | 3rd class municipality |

|

Location: |

Northeast of Cebu province, approximately 38 nautical miles from Cebu City |

|

Total land area: |

10,597 hectares |

|

Number of barangays: |

15 |

| Population: |

44,588 (NSO 2010) |

| Number of households: |

9,544 (NSO 2010) |

| Topography: | Gently sloping and rough terrain |

|

Annual income: |

P83.5 million (2014) |

|

Main agricultural products: |

corn, coconut, fruits, vegetables, livestock, salt and freshwater fish |

|

Major source of family income: |

crops farming, fishing, salaries and wages |

San Francisco’s purok system was developed by ex-Mayor Alfredo Arquillano Jr during his second term in 2004. (READ: 5 steps to disaster-ready, climate-resilient communities)

He started by encouraging one purok to solve its own solid waste management problem. That time, the town’s tree-lined avenues and fields were littered with garbage.

Eventually, other locals, inspired by the transformation of the first purok, began organizing themselves too. From handling only the garbage problem, the puroks took on other roles: maintaining roads and drains, planting vegetable gardens, starting livelihood projects and keeping peace and order.

A purok consists of 50 to 100 households geographically close to each other. There are 7 to 8 puroks in one barangay. In total, the town has 120 active puroks.

Each purok has an elected president and various chairpersons leading committees on health, solid waste management, peace and order, and more.

It is the creation of such committees – usually done only at the barangay level – which sets San Francisco’s purok system apart from the rest, according to an evaulation done by the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR).

Another cited strength of the system is that purok leaders report not only to the barangay chairperson, but directly to the mayor through coordinators. Purok coordinators manage groups of puroks – from 21 to 30 each.

They regularly check up on puroks to make announcements from the municipal government. Every week, they report back to the mayor any concerns or issues that are raised.

Desiree Llanos Dee, a former staff of the Climate Change Commission who was sent to San Francisco to assess their local climate change adaptation plan, said the effectiveness of the town’s purok system lies in its bottom-up approach.

“The system builds on existing indigenous social organization for mobilizing resources,” she said.

Through the different committees, “the purok system has become an intravenous system injecting solutions into the communities,” she added.

Being an island prone to typhoons, storm surge and sea level rise, it was inevitable that San Francisco would use the purok system for disaster risk reduction.

Today, puroks have committees dedicated to the task.

Puroks and disaster

The town has a digital and manual rain gauge given by aid group Plan International in 2009. When rainfall levels are beyond normal, the town’s Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office (LDRRMO) warns the purok leaders.

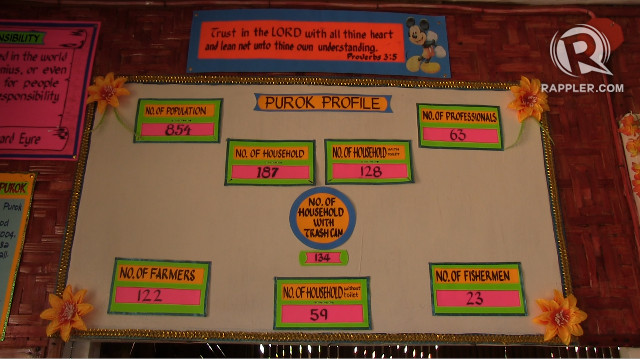

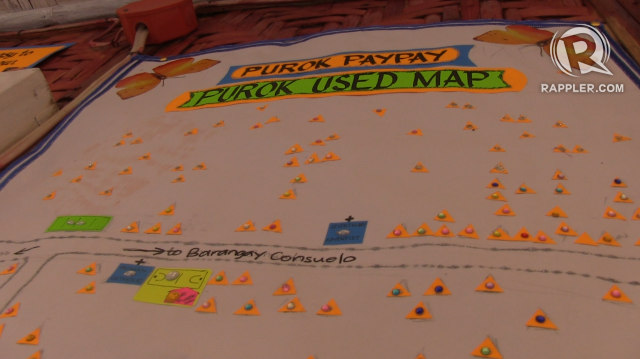

The most active puroks have maps and a purok profile that help them identify who in their community are the most vulnerable to specific disasters like typhoon, storm surge, flooding and landslides. This information tells them who to prioritize for evacuation.

All municipal grounds have access to a WiFi connection, allowing the LDDRMO to monitor typhoon tracks or tsunami warnings.

Once a disaster has been confirmed by state weather bureau PAGASA to hit the town, the LDDRMO calls a meeting of barangay officials and issues written advisories for preparation and evacuation, said LRRRMO Research and Planning officer Monica Tan.

The barangay officials are required to go around their village to make the announcement by megaphone. For their part, purok leaders ring bells placed in strategic parts of the purok to signal to their members that it’s time to evacuate.

The puroks make information dissemination – a make-or-break factor for disaster preparedness – much more effective.

“A barangay usually has a population of 2,000 to 4,000. If you only have the 25 barangay leaders, how can you spread information? The purok system makes it easier,” said Tan.

Disaster-readiness is further strengthened by typhoon drills down to the purok level. Two major typhoon drills are held the day before the anniversary of two major storms in the town’s history: Typhoon Bising in March 1982 and Typhoon Ruping in November 1991.

Yolanda and Purok Tulang Diyot

In the case of Yolanda, a well-updated LDDRMO and organization at both the barangay and purok level helped prepare the town.

Tan and her LDDRMO colleagues began monitoring Yolanda a week before. Aside from relying on PAGASA updates, Tan called a contact in Albay province, another LGU recognized for its disaster resilience, for more localized information.

The day before, Arquillano, who after his term continues to help the present mayor (his brother Aly Arquillano), took a boat to the PAGASA weather station in Mactan in the Cebu mainland to confirm Yolanda’s course.

Meetings were called involving barangay and purok leaders on the necessary preparations. Two days before Yolanda, based on instructions from the meeting, purok volunteers were already trimming and cutting trees that could fall and block roads. They were stockpiling relief goods and readying evacuation centers, most of which are school buildings.

The purok system in action is exemplified by the Yolanda experience of Tulang Diyot, an islet 10 minutes away by boat from San Francisco town’s main island.

“In Tulang Diyot, even without an advisory, the purok officers were ready because of communication with barangay officers,” said Tan.

“They didn’t need to wait for a barangay official to come to their aid. By Wednesday, two days before the storm, families were already being evacuated out of the island. By Thursday, everyone was evacuated,” she said.

The result? All 200 families living on the island were saved.

Replicable

It took 7 years for San Francisco to have 120 puroks. At first, people thought it was a waste of time since purok leaders serve on a voluntary basis and aren’t paid a salary.

To encourage puroks, Arquillano began a purok beautification contest. He set aside P600,000 ($13,700) of the municipal budget so he could award P20,000 ($456) each to those who could best implement solid waste management, conduct regular meetings, and plant a vegetable garden.

“One policy we emphasize is no dole-out policy. They have to earn it,” said Arquillano.

Puroks by themselves came up with a capital build-up model in which each member donated a set amount. The aggregated funds served as a revolving fund from which members could borrow emergency money. The members agreed on the interest rate. The money was also used for livelihood programs. This way, purok funds grew.

With the capital build-up and cash prizes, some puroks have more than P120,000 (US$2,700) in fluid assets. Fe Aris, president of Purok Bogo, said they used their funds to build a purok hall costing around P20,000 ($456).

Keeping a purok together, and on a purely voluntary basis, can be tough, said Aris. Fights can break out among members. Harsh criticism drives some leaders to resign.

But as Ryan Batidor, a former coordinator who has dealt with such situations before, said, “I congratulate purok leaders who draw criticism. I tell them about the mango tree. Kids only throw stones at a mango tree when it has borne fruit.” – Rappler.com

Have a good story to tell about a group or individual involved in disaster preparedness and response education? Email us at move.ph@rappler.com.

Check out the other case studies here:

- VIDEO REPORT: Disaster risk reduction in Camotes: The Purok system

- Tanay Mountaineers: A model of youth empowerment

- VIDEO REPORT: Tanay LGU and civil society work for disaster preparedness

- Pasig City: Learning from Ondoy, ready for the rain

The research for this case study was supported by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.