SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

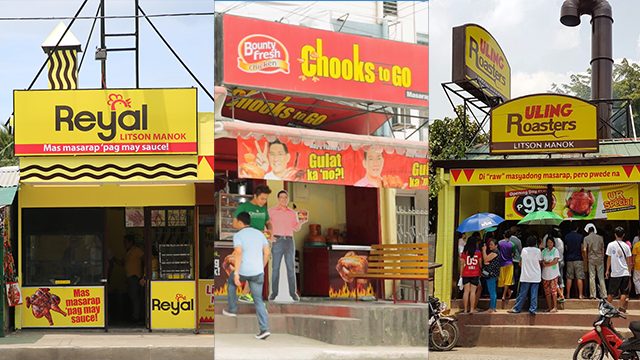

MANILA, Philippines– Along narrow city streets, bright signs of food kiosks call out to the hungry. But between the wide selection of food choices, Chooks-To-Go, Uling Roasters, and Reyal offer a Filipino favorite: lechon manok (roast chicken).

Though unassuming in appearance, when put together, these 3 kiosk brands make up Bounty Agro Venture Incorporated (BAVI)’s P10-billion business as of 2015.

Selling nearly 200 million chicken products yearly, BAVI feeds the monster Filipino appetite for lechon manok, growing a business with a turnover that eclipses the P8.5 billion of GMA Network, the country’s 2nd biggest broadcast group.

BAVI was not an overnight success. While a chicken egg takes about 21 days to hatch, BAVI took 15 years.

Chooks to Go: born from defense

BAVI is one of the Philippines’ largest poultry integrators, and caters to the Bountry Fresh group of companies, which, in turn, operates a network of rotisseries under the brands Chooks To Go, Uling Roasters, and Reyal. BAVI is also in the business of producing commodity chicken products – supplying dressed chicken to supermarkets, wet markets, restaurants, hotels, and its company-owned retail stores nationwide.

Founded in the 1980s by businessman Tennyson Chen, the company started operations in Sta Maria, Bulacan, with a layer farm of merely 5,000 chickens.

It was in 2002 when Chen wanted to take the company to its next level.

Seeking to professionalize and scale up the business, Chen hired Ronald Mascariñas, then president of Smokey’s, San Miguel PureFood’s fast-food brand selling a variety of hotdog products, and Senior Vice President of San Miguel PureFood’s Poultry and Food Service businesses.

Mascariñas built a team, most of them trusted colleagues from his previous roles, who then leveraged on their vast network of industry players. From this, BAVI’s nationwide poultry integration operations was born.

To accelerate growth and nationwide reach, BAVI engaged third party investors to build and operate a network of poultry farms, processing, and delivery operations, which follow company standards.

Over time, this nationwide network of contract farms and operations grew. BAVI currently produces dressed chicken, feeds, and finished chicken products for their retail stores, with 7 plant operations in Luzon, 8 in Visayas, and 4 in Mindanao.

Stable sales of commodity products, however, was short-lived.

Crisis came in the late 1990s as the ASEAN free-trade agreement rolled out and threatened BAVI’s commodity business. Bigger poultry producers in the region could offer the same products at a lower price.

“When we looked at our numbers compared to ASEAN, specifically Thailand because they are the biggest poultry producers in the region, we were scared,” Mascariñas said in an exclusive interview with Rappler.

For Mascariñas, the concern was on customer loyalty. “We thought of the logic: Why would supermarkets and outlets buy from us if they can buy it cheaper? Say the cheap poultry chicken from Thailand comes in, will our customers be loyal to us? They will not be. They will buy wherever the cheapest (product) is. Their loyalty is to the price.”

For the business to survive, BAVI decided the only option was to venture one step further. Instead of selling to customers who would cook these raw chicken products, or wholesale buyers who would sell these as ready-to-serve chicken products, BAVI decided to cut the gap and draw closer to end-buyers.

Out of defense, Chooks to Go was born.

“When competition disturbs our company’s direction, it challenges us to search for other opportunities to strengthen our position in the industry. The imminent challenge of cheaper chicken supply from competing imports with the implementation of the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) Agreement gave birth to Chooks to Go,” said Chen in a 2014 interview with marketing expert Josiah Go.

“That was a very clear direction: If we want to sustain employment for all of us, then we need to put up our retail stores,” said Mascariñas.

Winning recipe

Although the direction towards retail was clear, turning it into a reality was another battle.

Setting up a retail segment was an idea tried by the likes of San Miguel Pure Foods, Swift Foods Incorporated, and Universal Robina Corporation – national giants in the meat and poultry industry, but to no avail.

How, then, is a P10-billion business born? For BAVI, success came from an 80% failure rate.

At present, Chooks To Go is the market leader in roast chicken products with a network of over 1,000 stores nationwide. Competing with other lechon manok brands such as Andoks, Sr Pedro, and Baliwag, the company further distinguishes itself as the only brand to offer cooked chicken products without an accompanying sauce – something rarely offered by other food retailers in the Philippines.

BAVI’s retail business contributes to about 55% of the company’s total revenue. Mascariñas added that the company expects the number to go even higher this year, confident that sales will contibute to about 70% of total revenue by the end of the year.

But in its pilot phase, BAVI’s retail business was nothing short of a failure.

Setting up an initial 10 Chooks To Go test stores in Visayas, 8 of its stores sold no more than 10 heads a day. “At that time, the results were clear. There were daily reports that would come in. Weekly reports, monthly reports, and then a final summary after two months – there was an 80% failure rate. It seemed Filipinos did not want oven-roasted (chicken),” said Mascariñas.

With the seeming imminent end of the company’s proposed retail segment, Mascariñas decided to visit the stores a final time before closure. Witnessing slow sales came as no surprise. However, two of the company’s test stores in Ormoc and Tacloban offered what Mascriñas could only describe as overwhelming success.

“Akala ko, exaggerated yung kuwento – na grabe yung pila everyday. But true enough, ‘yung pila, talagang mahaba – Monday to Sunday. At ‘yung kakaiba doon, ‘yung pila, karamihan magbabayad ng pre-paid; bukas pa sila kukuha nung chicken. ‘Yung mga nakapila doon, binarayan na nila kahapon. Ganoon ka in-demand,” said Mascariñas.

(I thought they just exaggerated the story – that lines were crazy everyday. But true enough, the lines really were long, Monday to Sunday. And what was unique there was that most of who were lining were those paying for pre-paid orders – they would still get the chicken the next day. Those who lined up also paid the day before. It was that in-demand.)

The difference was in a decision of the manager of that store to change the product’s recipe.

“From the standpoint of product development, skipping (a step) was really needed. But from the science of it, you really needed that. And they skipped it. The result was a truly tasty product,” said Mascariñas in a mix of Filipino and English.

The step, as it turns out, involved decreasing the amount of water added to the product’s spice mix. In turn, a dry spice mix was opted for.

Stumbling on the successful recipe, Mascariñas ordered all stores to follow. “That night, I called all the other managers in Visayas and told them tomorrow, skip that step. And shortly after, sales went up.”

Convinced they found a winning formula, BAVI set out for a nationwide expansion of Chooks To Go stores. “How can I argue with success?” Mascariñas said, grinning.

Tried and tested

In the process of expansion, the new retail brand faced another test: resistance from BAVI’s own management team.

Mascariñas shared that convincing management of the decision to expand into retail was a challenge. The overwhelming question from BAVI’s management was “Kumikita naman kami, boss. Bakit kami papasok sa ganyan (We’re earning anyway, boss. Why would we enter in something like that [retail])?

As BAVI supplied commodity products to supermarkets, wet markets, and institutional buyers, putting up a retail business meant competing with their own customers.

“That was the dilemma. But I told management that the direction of the company is very clear: We will put up our own retails stores for roasted cooked products and dressed chicken. Now, if we’re dealing with a business partner who cannot work with our direction, they are free to leave,” said Mascariñas. It was a threat that worked.

The aggressive nationwide expansion of Chooks To Go started in 2008, eventually reaching a network of nearly 1,200 company-owned stores nationwide.

But in 2011, BAVI would face yet another setback.

“It looked like we were going to lose the brand (Chooks To Go). Income was really going down….We were really scared,” shared Mascariñas.

The company was plagued by undercooked and spoiled chicken products, which in turn drove down sales and led to the closure of nearly 50% of its stores. In 2011, net income reached only P48 million, down 54% from the previous year’s P74 million.

BAVI hired United Kingdom-based consultant firm, Renoir Consulting Limited for $1 million to help them learn and move forward.

After a year of ironing out operations and management kinks, BAVI was on a roll again.

It decided to set up its second brand, Uling Roasters, which sought to capture market demand for charcoal-roasted chicken.

In 2015, the company set up its 3rd brand, Reyal – this time setting out to capture the market’s appetite for chicken products that come with a sauce. “In most countries, and it’s true in the Philippines, whether fastfood or roasted chicken market, it (products) always comes with a sauce. Go to McDonalds or KFC… (they even serve) unlimited gravy. So we know there’s a market for that,” said Mascariñas.

Mascariñas believes that among the company’s brands, it is Reyal that has the potential to overtake Chooks To Go as the market leader. “In [the] roasted chicken [market], our biggest competitor is practically ourselves. We let the 3 brands compete with each other; it’s something that we own already,” he said.

BAVI recently announced that the company would again set out on massive expansion efforts, seeking to open up to two stores a day across its 3 brands. Mascariñas maintained that all stores would remain company-owned in the interest of seizing prime store locations while keeping operations and quality consistent.

Likewise, Mascariñas believes BAVI will saturate the market for cooked chicken products in two years. The company even boasts a presence in Sulu and Tawi-Tawi.

BAVI currently operates about 1,800 stores across the 3 brands and has set an ambitious target of about 2,300 stores nationwide by end-2017.

To add to its portfolio, BAVI is currently testing two new brands: Snock and Kamukamo, a snack line and pork product line, respectively.

Next chapter

The ASEAN crisis that drove BAVI to fight for its survival is no longer a looming threat.

Mascariñas credited BAVI’s success to the people who manage the company’s production and operations. “What we thought would be an advantage to them – the technology, low cost of raw materials, etc, it’s not showing up because at the end of the day, people will use the technology. The best people in the industry – we really pounce on them. We make sure they’re with us,” he said in a mix of Filipino and English.

This time, BAVI takes on a new challenge: regional expansion for its first brand, Chooks to Go.

“If you look at what we’re doing, it’s not rocket science. There’s nothing extraordinary about it,” said Mascariñas.

Recently, BAVI set up two Chooks to Go stores in Malaysia, its first location outside the Philippines. Mascariñas shared that once the company learns how to operate in an international setting, it plans to open its second foreign location in Indonesia by the end of the year.

Mascariñas also shared BAVI has a list of interested partners in South Korea, Canada, and West and South Africa.

“We should be the McDonald’s of roast chicken,” Mascariñas said, oozing with confidence. — Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[In This Economy] Is the Philippines quietly getting richer?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/20240426-Philippines-quietly-getting-richer.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=194px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[In This Economy] A counter-rejoinder in the economic charter change debate](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/TL-counter-rejoinder-apr-20-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=267px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Vantage Point] Joey Salceda says 8% GDP growth attainable](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-salceda-gdp-growth-04192024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[ANALYSIS] A new advocacy in race to financial literacy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/advocacy-race-financial-literacy-April-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.