SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

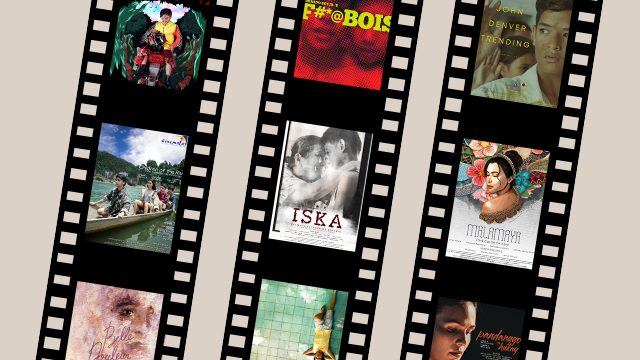

ANi (The Harvest) review: Rusty all over

The biggest problem of Kim Zuniga and Sandro del Rosario’s ANi (The Harvest) is that it obsesses over the most insignificant element of the film, which is the titular robot. What is even more frustrating about the film is that despite the obvious attention given to animating the robot, it still looks dodgy and barely comparable to second-rate special effects from a low-rent and micro-budgeted videogame.

When a film that has some smart idea ultimately suffers because of a disastrous infatuation with technology that makes it a clear product of the present, it exposes the filmmakers as stifled and immature, more inadequate craftspeople than flexible artists.

ANi (The Harvest) is less than half-baked. It is mashed and mangled.

Its story, which is hardly complex or complicated, is chopped to questionably arranged pieces all for the sake of sporadic scenes supposedly meant to astound with a haphazardly designed robot doing all sorts of tricks that result in the faintest of amusement.

What’s left of ANi (The Harvest) are echoes of the film that it could have been had the filmmakers decided to graduate from showing off their attempt to ape big-budgeted special effects with very meager resources. There are fine ideas here and there. The entire dystopian conceit of militaristic conglomerates taking over farmlands could have been the film’s bid for relevance. However, that has been eclipsed by the preponderance of such mediocrity. The writing is shallow. The performances, especially by the Zyren dela Cruz as the orphan who befriends the titular war robot tapped to quell a growing farmers’ rebellion, are bland and uninspired. The least ANi (The Harvest) could have done is to be heartbreaking even in the most manipulative of ways, yet despite having most of the elements of a formulaic tearjerker, the film ends up more annoying than affecting. The film is just rusty all over.

F#*@bois review: When push comes to shove

In a way, F#*@bois is a departure for Eduardo Roy, Jr., whose films are focused on shining a light on the lives of the silenced and the marginalized.

In following the stressful routine of the overworked nurse who is the center of Bahay Bata (2011), he showed glimpses of the various stories of all mothers crowding for beds and medical attention in a public maternity hospital. In Quick Change (2013), he managed to bring to the fore the plight and yearnings of a transwoman peddling illegal beauty injections. Even his first foray into escapist rom-com, Last Fool Show (2019), skirts the typical glamour of movie-making by mining romance out of the inglorious creative process of a screenwriter. F#*@bois is different in the sense that its young protagonists are fame whores, victims of a contemporary preoccupation with always being seen, with being constantly relevant even if it is for the most banal of reasons.

Yet F#*@bois is also familiar in how it navigates the hidden lives of its titular characters. While Miko (Royce Cabrera) and Ace (Kokoy de Santos) aren’t depicted as beholden to the flesh trade for survival given that they are garbed not in rags but in designer clothes, their struggle within the narrative of the film remains to be staunchly a power struggle between the haves, as represented by the ex-mayor (Ricky Davao) who blackmails the boys with a video scandal, and the have-nots, as represented by the boys whose paraded identities will be drastically tainted by the content of the video. What could be the film’s most interesting element is the fact that its events happen during election time, where the politicians’ lives are at the mercy of the have-nots.

Roy subtly pushes for the political undercurrents of the familiar premise and with his film’s ending that borders the cryptic, absurd, yet definite in its implication, arrives at both a scathing and empowering depiction of a generation whose concerns revolve around the inconsequential but has the power to overthrow authority when push comes to shove.

Iska review: Stuck and marooned

Theodore Boborol’s Iska opens with grating noise. Amidst the cacophony of the slums in the morning, an underwear-clad boy is crying relentlessly while Iska (Ruby Ruiz) is trying to calm him and dressing him up at the same time. The scene is stretched for a minutes longer than necessary, perhaps to prepare the audience to fortify its tolerance for blunt chaos, which is somewhat smart, as the rest of the film is mostly composed of elegantly staged commotions that supposedly forward the agenda of shining a light on the little people that pepper the country’s foremost university.

Boborol weaponizes irony, pitting the gnawing misfortunes of the most invisible and undervalued component of the university with the social activism that the university has become known for. Iska attempts to tackle the gap between what it perceives as harsh reality and shallow advocacy, focusing on the wide disconnect between the resilient victims of all the social inequities and those who are supposedly representing their cause.

Iska is fueled by bleakness and melancholy. Ruiz, thankfully, is an astute actress and does not rely solely on telegraphing the unbearable trials of her character’s life. There is important levity in the performance, which is at times problematic given the seriousness of some of the film’s episodes.

Nevertheless, the film could have been a harrowing and possibly torturous experience that drives a critique of student activism grounded on simplistic and manipulative storytelling. Thankfully, Ruiz steers the film to become not just another expose that is harping on the wrong tree but also a masterclass in thoughtful and sensitive acting, adding glimpses of true humanity in a character that is written to be a foil for society’s hypocrisy and insensitivity.

Malamaya review: Blank canvas

Drab and dreary aren’t the adjectives one would like to see attached in a film about art.

Sadly, Danica Sta. Lucia and Leileni Chavez’s Malamaya is exactly that — drab and dreary. The film tackles the complicated relationship between a middle-aged artist (Sunshine Cruz) and a young photographer (Enzo Pineda). This isn’t to say that the film is without any ideas because if there is anything that the film is successful in doing, it is its exploration of the often distant and eccentric art world through the hesitant eyes of a woman brimming with sexual needs. Sure, Malamaya ends up drab and dreary with the impenetrable performances of Cruz and Pineda to blame but it does the job of humanizing creativity.

If anything, Malamaya is interesting because it dares to appropriate art as a diving board for its ideas. Its camera lingers thoughtfully, often dwelling on the various art pieces, whether they be a glorious painting or a performance piece. It is almost as if the film borrows all the art it surrounds itself with to create a palpable atmosphere of sophistication. Whether or not there is something beneath and beyond the film’s preoccupation with creativity or that everything is just a blank canvas that has remain unutilized up until the end is a totally different matter. What is certain is that the film is cleverly curated and functions as a sure-footed portrait of a creative at work, no matter how hollow the narrative that adorns it is.

Children of the River review: Shallow but shaky waters

Maricel Cabrera-Cariaga’s Children of the River has a fine premise. In a remote town meant to house the family of soldiers, a group of friends are coming of age. Perhaps the clincher in what appears to be too generic a conceit is that taciturn Elias (Noel Comia, Jr.) is now coming to terms with his sexuality when a visitor comes to town.

In a town of absentee military fathers, the murmurings of Elias’ heart which seems to go against the stereotypical patriarchy that defines the community become the film’s most compelling element. Sure, Cabrera-Cariaga bludgeons the concept with unadorned sweetness and Comia occupying the role with just enough tenderness to make the character’s qualms about confronting his sexuality affecting.

However, what lurks beneath the somewhat sweet yet very shallow waters of Maricel Cariaga’s Children of the River is a very confused position. What is starkly bewildering is for a film that manages to be so faint and understated when it comes to the burgeoning sexuality of its main protagonist, it belatedly becomes blunt in echoing a military stance. The messaging is garbled.

The film could have used the community of military families as a premise to enunciate the primacy of self-discovery but instead, it decides to kowtow to easy sympathies and sentimentalizing patriotism, to throw away all it has achieved in sensitively portraying a boy’s blossoming despite the shadows of institutional patriarchy all for the sake of sending mixed signals about armed conflict. — Rappler.com

Francis Joseph Cruz litigates for a living and writes about cinema for fun. The first Filipino movie he saw in the theaters was Carlo J. Caparas’ Tirad Pass.

Since then, he’s been on a mission to find better memories with Philippine cinema.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.