SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

He had said “Daghang salamat,” Cebuano for “thank you,” in our group chat days before, and he could in fact be mistaken for a mestizo, so just in case I had formed assumptions about his background…. He does speak Cebuano, though, but “gamay lang (just a little).”

There was as much pride as kidding in his greeting, actually. There is a part of this 42-year-old that is Filipino. That was why, while his only experience in “published” writing was the musings on life and society that he occasionally posted to his Facebook account, he agreed to do the storyline for the manga series Jose Rizal.

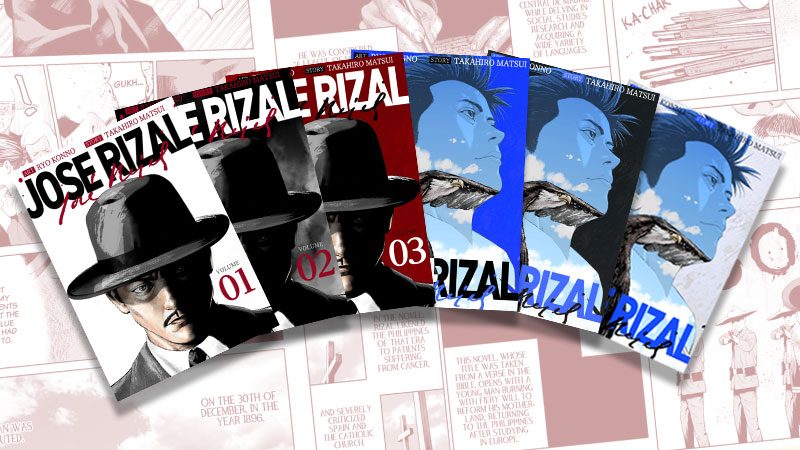

Yes, that manga whose teaser video gave us goosebumps with the Tagalog version of “Mi Ultimo Adios” set to Anne Mendoza’s Naoki Sato-ish music; that online Japanese comics, which was launched last June 19, the 157th birthday of the Philippines’ national hero.

Bullied kids

Matsui spent 3 years in Cebu as a partner of the Philippine Department of Education. He supervised the teaching of Nihongo in public high schools in Central Visayas as part of language electives under the K to 12 program.

That was when Rizal started to pique his curiosity. Why did the portrait of this man hang on the wall of practically all the classrooms he’d been to?

Back in Japan by 2014, his day job involves running the international lounge in the Tsurumi ward of Yokohama, which offers services to help migrants understand Japanese culture so they can adapt as smoothly as possible to their new home country.

A number of the children they serve are Filipinos, from whom he’s heard stories of being bullied by Japanese classmates for their roots.

“There are a lot of kids with Filipino roots here in Japan. They don’t want to be bullied or racially discriminated. I hear these stories in consultations [with children and parents] all the time,” he told Rappler in Japanese.

Many of these children don’t even want their Filipino parents to come to their school, because if their Japanese classmates see how non-Japanese their parents are, then the more they’d get bullied for it.

“I wanted to encourage them, to tell them, no, you’re not any less of a people. There’s this one fine, really amazing person from the Philippines that you should be proud of,” Matsui said. “And the Japanese school kids should realize that too.”

A walk in the park – literally

Meanwhile, about 40 minutes by train from Yokohama, in Tokyo’s Hibiya Park, the other part of the story was unfolding.

Takuro Ando, the president of the online book seller and publishing company Torico, “happened to walk around…and found this interesting bronze statue.”

It was the bust of Jose Rizal, which was erected in Hibiya Park on the spot where the Tokyo Hotel used to stand. Rizal had stayed there in 1888 on his way to Europe.

“I searched his name on the internet and found out that he is the Philippines’ national hero,” Ando said in a video taken to answer the questions sent by Rappler.

“I immediately thought about what would happen if this legendary person returned as a manga hero that could be enjoyed by people all over the world, including the Philippines.”

While Torico had been in the book selling and e-book publishing business for more than a decade, it created Manga.club only in November 2017. The site is where the company uploads choice titles to be accessed by fans for free or through limited tickets. This is where the Rizal manga would later be uploaded.

“But even before I established Manga.club,” Ando said, “I had always been very determined to spread manga culture to people around the world. Every day I never stopped thinking new ways of reaching new fans.”

Rizal’s “fascinating tales,” the “many ups and downs in his life,” would “surely captivate everyone regardless of the nationality,” he thought. “That’s why I initiated this project.”

They embarked on the project in January this year.

Ando asked the award-winning manga artist Shuho Sato (of Umizaru and Say Hello to Black Jack fame) to recommend 3 of his apprentices to draw the manga they would simply call Jose Rizal. Among them, Ryo Konno was chosen.

A visit to Calamba

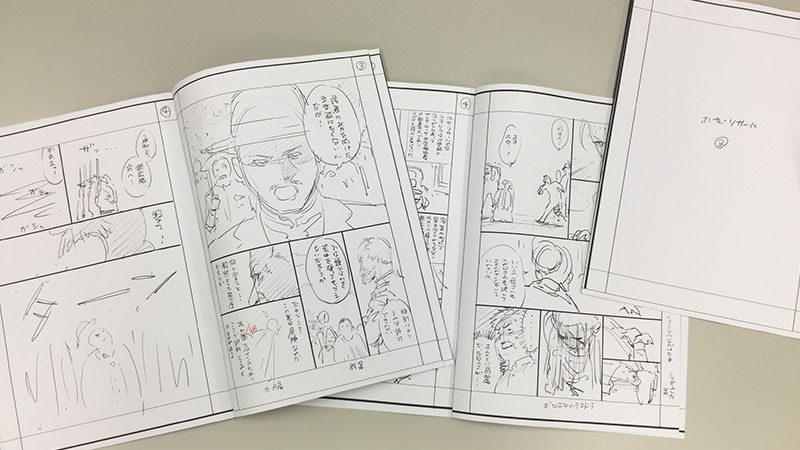

Konno, 30, has been drawing manga for a decade now, about 4 years of that professionally. Jose Rizal was his most challenging so far.

“Up until now, I have been working on mangas which are set in Japan. This time it is set over a hundred years ago during the Spanish colonial era in the Philippines, so I was extremely careful to draw it in such a way that there would be no sense of discomfort among Filipinos,” Konno said in Japanese.

To be accurate, the artist did his field work. For 4 days, he went around Rizal’s birthplace in Calamba, a city in the province of Laguna, some 50 kilometers south of Manila, and in the Philippine capital itself. Aided by local interpreters, he visited and took photos of the places that would be featured in the series, and reimagined how these looked like in the 1800s.

In Calamba, Konno recalled, city hall staff were unfortunately not very familiar with the details he wanted to know, and he didn’t get to talk to Rizal’s descendants either.

The locals and his translator, however, were helpful. “People could tell you where it happened – the jail [where they locked in Rizal’s mother] is still there, but it’s now a marketplace. The house where Rizal grew up is already a museum,” he said.

Illustrations for the opening scene of Chapter 1 – Rizal facing the firing squad – were based on materials he gathered in his visit to Luneta.

“I thought that it was good that we were able to collect data directly, because there were differences between the materials we had at hand and what we found out when we asked a local,” Konno said.

For example, it had always been assumed that when the Governor General visited Laguna and was accorded a lavish party, it was inside the cathedral.

This was the occasion where Rafael de Izquierdo, pleased with the dance performance of Rizal’s sister Soledad, asked her to make any request and he’d grant it. The girl asked for her mother, Doña Teodora, to be set free. We read about this in Chapter 3.

“In fact, the party was outside the church – they just built a stage there,” Matsui said.

Reading Rizal – in Japanese

Did Matsui read Ambeth Ocampo, the Philippines’ foremost authority on Rizal?

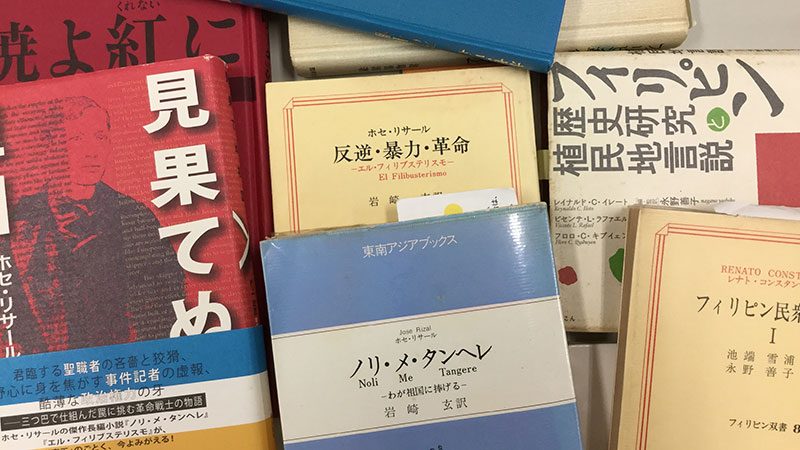

He admitted that he had heard of the scholar, but since all of Ocampo’s work were in English, it would have taken him time to read him. Thankfully, there are works by other Filipino authors and Japanese researchers available in Nihongo.

At Matsui’s office, these reference materials still proudly bear post-its and notepads doubling as bookmarks from when he was writing the manga. There’s Carlos Quirino, Renato Constantino, Japanese translations of Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, among them.

He acknowledged that it was difficult to summarize in a few manga volumes the life of such a complex man in a crucial historical era, but getting a grasp of Rizal’s thinking was an adventure and enlightening experience in itself.

“I know there were questions about about his nationalism, debates about whether he was a revolutionary…but maybe Rizal opposed a revolution because there were other solutions,” Matsui said. “I was most moved by how he also cherished people, equality, and freedom.”

Matsui isn’t sure if he’d write another manga, now that he’s tried his hand at it, but if only for having learned this much from Rizal, he is grateful. “To write this one manga was already a blessing,” he said.

He goes back to what made him agree to write the series: “I want the children with Filipino roots here in Japan to know more about their roots, about Jose Rizal, and let them become proud of their own roots.”

Konno, for his part, found affinity with Rizal in that they were both creators who wanted to make a difference: “I can strongly sympathize with wanting to change the world through our works.”

Will more manga follow?

Torico is testing how the manga enthusiasts and the international market are receiving this experiment. Its titles have always tackled action and romance. Jose Rizal is its first publication that’s historical and biographical in nature – about a non-Japanese, in another country, at that.

Jose Rizal is listed under “Seinen.” Translated as “young man” or “young men,” seinen is a subset of manga targeted at male readers 20-30 years old. At times, titles are also published under it for men in their 40s.

Readers are given a choice to read the manga in English or in Japanese (click the flag of either country on the screen to do that). And as with any manga published in Japan, even the online version is read from right to left of the pages.

There seems to be growing interest in the series. While only 4 chapters were originally announced – each released every Tuesday starting on June 19 – you’d see now on Manga.club that a 5th and 6th ones have just been added. If things turn out well, the company said, fans can probably expect up to 10 chapters.

Because, the writer pointed out, why would the humanism embodied by the Philippine national hero not appeal to any person, regardless of race? In the end, Matsui said of Rizal’s story: “It’s not about being Filipino or Spanish, or even Japanese. It’s about humanity.” – Rappler.com

Translations during the interviews were provided by Phyllis Kimberly Tanmo.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] ‘Barbie’ awakens: A response to the film being called ‘woke propaganda’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/08/barbie-imho-aug-1-2023.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Why is Japan Home Centre accepting sibuyas as payment?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/02/japan-home-center-february-3-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=188px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.