SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

On June 9, 2019 Philippine fishing boat Gem-Ver was anchored near Recto Bank, ready for deep-sea fishing in the West Philippine Sea. They planned to remain there for 12 days. On the 9th day, a Chinese vessel rammed, sank, and abandoned Gem-Ver and its fishermen in the open seas in the dead of night. The Philippine government has since downplayed the incident, even casting doubt on the account of the Filipino fishermen.

Rappler spoke to all 22 fishermen of Gem-Ver who agreed to put their testimonies on the record. This is their story.

I. Calm before the storm

It was close to midnight in the deep of the West Philippine Sea that spans the side of Palawan and Mindoro islands. Cradled by the crescent moon and the soft waves that began to lull them to sleep, Filipino fishermen prepared to anchor their beatdown boat and rest. They had been at sea for 9 days.

The cook, Richard Blaza, made sure they’d be ready for the morning ahead. Standing at the rear of the boat, he scanned the stacks of dried fish that he had been cooking for hours in his makeshift kitchen. He was tired but pleased. The men will be up at 3 am, eat breakfast, and pack their lunches into the smaller boats that will lead them to another day of hauling.

It was June 9. They all yearned for home in the coastal town of San Jose in Occidental Mindoro, hundreds of nautical miles away. But they had so far managed to catch only 3 tons of fish, one ton less their target. This would not be enough for the boat owner and for themselves, as there were debts to pay and families to feed back home – until the next sail.

The calm summer night offered some refuge.

Boy Gordiones lay on his back half-awake, dropping a fishing line as he stared at the stars in the sky. As the boat’s mechanic, he chose to rest in front of the cabin, right below the windows where the captain usually looked out to the horizon.

The captain, Junel Insigne, slept inside, sharing the boat’s only room with Boy’s two sons, Jomar and Jaypee. Fast asleep by the foot of the cabin’s starboard door was Edgar Martinez, one of Gem-Ver’s veteran fishermen.

Atop the cabin, 9 men slept next to each other: brothers Frederick and Jeffrey Roldan, their cousin Mark, Ramil Agustin, Melquiadez Tiamzon, Arnel Gadon, Bannie Condeza, Justine Pacaul, and Joven Jacinto.

On the roof of Richard’s improvised kitchen slept 7 others: Ramil Gregorio, his son Jimuel Gregorio; his cousins, the brothers Lim Gregorio and Lemuel Gregorio; and middle-aged fishermen Antonio Torres Jr, Cirilo Escuterio, and Regan Sta Maria.

All in all, there were 22 of them.

Richard took one last peek at the iron pot of steaming rice that he would be serving in a few hours, then walked to the tail of the boat to sleep.

Just as he was about to doze off, he heard something.

II. Hum turns to roar

It all happened within seconds. What started as a deep hum of an engine crescendoed to a roar. Richard stood up, scoured the horizon, and saw it from the portside: a blur of a vessel at least twice the size of their wooden floater, its faint fluorescent cabin lights open.

Richard, the cook, ran and shouted to wake up the men sleeping nearest him, barging into the captain’s room to rouse him from sleep.

Junel Insigne jumped from where he slept below the helm and scrambled for the boat’s key on the dashboard. The captain had to move the boat away from the giant vessel’s path. The rest of his men ran toward the front of the boat, where they saw the big vessel rampaging towards them.

“Barko! Barko! May babanggang barko! (A ship! A ship! There’s a ship about to hit us!)” the men shouted over each other.

They saw the ship rush to the part between the boat’s back and the middle. Some of them jumped off to safety. At this point, Junel struggled to start the boat’s engine. But it wouldn’t start, and in a snap the vessel rammed Gem-Ver in its rear, forcing the wooden boat to twirl. The smash sounded like hundreds of bones breaking, leaving a gaping hole at Gem-Ver’s tip. Water gushed out from the bottom.

The Gem-Ver crew dropped to the floor to avoid the ramming vessel’s “horns” – metal cranes that extended beyond its body. The horns ripped through Gem-Ver’s two masts, toppling the boat’s fragile light towers. Several smaller boats attached to Gem-Ver fell into the water.

Jomar Gordiones got thrown off the boat. His father Boy was not bothered; he knew Jomar would be able to swim his way to the smaller boats hanging from Gem-Ver. As the one in charge of the boat’s machine, Boy had to keep the motors alive so he raced down the steps to activate the water pump and slow down the sinking. It was too late. The sea had swallowed the hull.

Then something happened. The metal boat stopped, turned around, and beamed what looked like hundreds of lights that, in the words of one of the fishermen, could light an entire village.

“Ang lakas ng ilaw, buong barangay namin puwedeng pailawin,” recalled Justine Pacaul. “Parang fiesta.” (The light was so strong it could light up our entire barangay. Just like a fiesta.)

Junel said that he and his men were blinded by the lights. “Silaw kami sa sobrang liwanag…sa dami ng ilaw na ‘yun,” Junel said. “Nasilaw kami sa sobrang liwanag at nasa madilim sila.” (We were blinded by the overpowering light…there were just so many. We were blinded by the overpowering brightness and they were in darkness.)

The lights unmasked the vessel: it was steel, its skin dark blue. Long metal horns branched out from its two sides. Twin masts connected by a beam towered on both its bow and stern. The generous lights hung over the entire stretch of the ship’s body.

The fishermen had seen this type before. It was Chinese.

III. Left to sink

When the bigger ship turned around after the blow, the crew of Gem-Ver thought it was moving to rescue them. “Ay, salamat (Thank God)!” Siloy Escuterio recalled shouting as the Chinese vessel came nearer.

The fishermen waved frantically, held open their palms, and made all signs of calls for help. “Saklolo (rescue us),” the Filipinos shouted.

Two of the youngest crew members, 21-year-old Justine and 31-year-old Jaypee, were able to get into their smaller boats after the impact and rowed closer to the vessel, hoping for help.

“Tulong!” Justine shouted as he looked up at the vessel. He saw the shadows of crew members standing atop its deck. He couldn’t recall how many they were, only that they stood still. After about 3 minutes, the metal ship turned off its lights then sped off.

“Akala namin masasalba pero iniwan kami,” recalled Antonio Torres. “Takot na ’yung naramdaman ko. Baka walang maka-rescue sa amin.” (We thought they were going to rescue us but they left us instead. I started to feel scared. No one might rescue us.)

If the Chinese did not mean to hit us, asked Jimuel Gregorio, why did they leave us?

Battered and sinking, Gem-Ver started to lose its lights. The men perched on its skewed tip were losing space to the sea. They saw death.

“Mamamatay na… akala namin katapusan na namin,” Junel said. As the sea slowly swallowed the boat, it also took back everything the fishermen caught in the last 9 days, as well as their phones, clothes, and fishing tools.

Jomar Gordiones lost his wallet which held his only photo of him and his wife a year after they got married.

To Junel, there was no time to waste. He barked orders to his men who sat cold and tight in the boat’s bow and cabin roof. They tied to the boat the two barrels of clean water that had been thrown out and were floating nearby. They set aside all the small boats and the water drums. “Safety na, itabi ‘nyo para sa atin,” Junel said. (Keep them safe, put them aside for all of us.)

Thinking this would keep his crew afloat for a few days, Junel looked far into the endless sea and found hope. From a long distance, a light shone the brightest.

IV. The men of Gem-Ver

About 5 feet, 5 inches tall, 46-year-old Junel Insigne stands as the quiet captain of Gem-Ver. He has been at the helm of the boat for the last 4 years, plotting the coordinates to the West Philippine Sea each month that the crew went on a fishing voyage.

Junel and his crew all hail from San Jose in Occidental Mindoro, in two villages that mirror the contrasts of an urbanizing town, where one part is choked with fast-food restaurants, convenience stores, and diners, while the other plays host to small resorts, sari-sari stores, and a line of fishing households.

Barangay San Roque lies in one of the biggest curves of the coast, where inner roads lead to labyrinths of shanties and half-finished homes. Lining one narrow passageway are the homes of the Insigne and the Giordones families. A few streets down live 10 other Gem-Ver crew.

An hour-and-a-half away by boat ride from the town center, and separated by farms of seaweed, is the village of Natandol. No more than an estimated 1,000 residents live here, sharing a chapel on a hill surrounded by patchworks of bamboo, flattened wood, and rusting metal sheets they call home.

Among those who live in Natandol are the Roldan brothers, Frederick and Jeffrey, and their cousin Mark. Just a few steps away is the bamboo home of Justin Pacaul, who married a relative of the Roldans. A short trek farther away are the houses of the Gregorios – brothers Lim and Lemuel, and the father-and-son tandem of Ramil and Jimuel.

At a young age, they knew they were destined to spend most of their lives on water. Their fathers were fishermen, and so were their grandfathers. The fishermen are seldom in their villages. For most of the year, home is above the waters of Recto Bank where they catch the best fish.

They would set out to sea and stop after a day in Culion, Palawan, where they refill their drums with clean water and make phone calls to their families before heading out deeper into the ocean. They sail for two days more before reaching Recto (Reed) Bank.

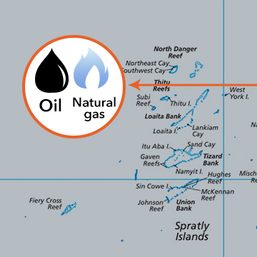

Approximately a hundred nautical miles off the coast of Palawan, Recto Bank is within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone and its continental shelf. International laws dictate that only Filipinos can fish there. For years, Filipino businessmen have been wanting to tap into its rich oil reserves.

The fishermen’s days in Recto Bank, which is a large tablemount, or guyot, begin before sunrise. They rise at 3 am, eat breakfast, and fix their equipment. The mother boat Gem-Ver drops them at certain parts of the deep ocean, scattered across a two-mile stretch.

By 6 am, each fishmerman is already rowing and scouting for his own abundant patch of water aboard his kawil, a kayak-sized wooden boat that fits only one person and his tools: hundreds of feet of nylon strings as his line; hundreds of white chicken feathers as his bait; and hundreds of fist-sized stones to keep the trap below the water’s surface. When he feels a tug, he pulls.

Days in Recto Bank end with a tally of each crew member’s haul. Richard, the cook, then weighs the catch on a scale, while Junel records what it registers. It’s the total in the captain’s notebook that determines when the work is done. The trips usually last 15 days. If they don’t reach their mandatory 4 tons of fish, they stay longer at sea.

V. Rowing to rescue

Justine Pacaul has been sailing with Gem-Ver only for a year. At 21, Justine is painfully shy and looks down whenever he speaks. On the night of June 9, his crewmates entrusted him with their lives.

After the smashing of Gem-Ver, Justine was partnered with the 31-year-old Jaypee Gordiones, one of the more outspoken and cheerful of Gem-Ver’s men. Together, they paddled their way to the vessel that would eventually rescue them.

Before they left the sinking boat, Jaypee’s younger brother Jomar handed him a plastic Coca-Cola bottle so he could use it to dip out water from their small boats. The two rowed against huge waves and strong winds. It was 2 am when they set sail toward the light in the distance, estimated to be some 5 nautical miles (9 kilometers) away. They hoped to reach the light’s source before sunrise.

The pair could barely see each other’s silhouettes in the dark – Jaypee was ahead, while the younger Justine trailed him. Jaypee was the quick rower, and he would repeatedly shout at Justine to paddle faster. “Huwag mo akong iwanan (Don’t leave me),” Jaypee would say.

At the wreckage, the men grew nervous as a radio call earlier in the day had warned them of 4-foot waves coming in the morning. Wet and cold, they sat and prayed in silence. Jomar recalled asking God to help his brother Jaypee reach the other boat.

“Panginoon, makahingi ng tulong. Tulungan mo po sana kami. ’Pag walang nakakita sa amin na tulong doon, wala na po. (Lord, help us. If they don’t get any help there, that will be our end.)

Bannie Condeza sat on the boat’s edge and prayed too. They kept the microlights of their lighters on, holding them up so they could beam and help the rowers find their way back.

VI. ‘Vietnam. Philippines. Friends.’

Two hours after they left the Gem-Ver wreckage, Justine and Jaypee came close to the light that they had seen from afar, seeing a familiar vessel marked TGTG-90983-TS. They had seen it a few times before.

His hands shaking, Justine cast his tired gaze at the ship before them, anxious that, like the Chinese hours ago, this foreign ship would also abandon them. He dreaded the thought, because he doubted if they would still have the energy to row back by themselves. “Hindi na kaya. Kung babalik pa kami na walang tulong, hindi na kaya,” he said. “(We wouldn’t have been able to do it anymore. We wouldn’t have been able to return on our own without help.)

Justine planned to climb the boat and wake up the men in the other ship. Jaypee did not think that was a good idea, fearing they’d scare the Vietnamese who might end up shooting them. Both ended up playing safe by shouting, “Vietnam, help me!”

The Vietnamese stood in their ship when they heard the cries, peering over the side of the vessel. To illustrate that they had rowed from a boat that sank, Justine and Jaypee scooped up water into their boats as they looked up to the Vietnamese above. Jaypee was crying. The Vietnamese threw them flashlights so they could see the two more clearly. Then they dropped a nylon cord and gestured for Jaypee and Justine to come aboard.

On the ship, Justine connected his two index fingers as he said: “Vietnam? Philippines? Friends.” The Vietnamese replied, “Okay.”

The sail back to Gem-Ver took longer than expected as Justine and Jaypee were unsure of the way back. With the same flashlights, Justine and Jaypee pointed the Vietnamese to where they believed they came from. It was Justine’s turn to cry.

An hour later, they managed to find Gem-Ver, the men already tired, cold, and hungry. It had been about 5 hours since the ramming. Justine and Jaypee quickly asked the others to come on board.

The Vietnamese out on the deck aimed their flashlights on the waters. As they assisted the men, the Vietnamese spotted Jimboy, Gem-Ver’s dog, which somehow managed to escape the boat moments after it was hit and made his way to the top of the cabin’s roof. They rescued Jimboy, too.

It was all hand language from there.

The Vietnamese gave the Filipinos dry clothes and served them chicken, noodles, rice, and biscuits. They laughed that their guests refused to eat with chopsticks. They showed the Filipinos what they were watching on the phone, a Jet Li film (White Snake).

Grateful, the Filipinos offered to help with the fishing. No, the Vietnamese gestured, just eat and sleep.

VII. Coming home

When the sun burst in the horizon, Junel sent out a call for help to fellow vessels from the Philippines. The alert was picked up by Filipino fishing vessels nearby. Fishing boats Gem-Ver 2, AG Thanksgiving, Thanksgiving 5, and Jovens responded to the call.

By 5 am of June 10, news of the incident had already reached San Jose. Wilson Mahinay, captain of the M2M fishing boat, received the bad news from a homebound Filipino fishing vessel. Seeing he had enough men and equipment, Wilson left the shores of Barangay San Roque at 10 am, along with Gem-Ver’s owner Felix dela Torre and Felix’s cousin Alvin.

“Walang dalawang isip. Takbo kami. Sana makarating kami kasi maraming tao nakahintay sa amin na nasaklolo (We didn’t think twice. We rushed. I hoped we could reach them because there were many people in need waiting for us),” Wilson said.

Winds bellowed and waves whipped M2M, but this did not deter Wilson, who vowed to sail non-stop until they saw Gem-Ver. After leaving the shores of San Jose that morning, Wilson radioed the Philippine Navy. “Scanner, mag-rescue kami.”

M2M sailed for 46 hours straight. Fishing boats Gem-Ver 2 and AG Thanksgiving were the first to arrive at the spot at about 2 pm of June 10. The Vietnamese handed the men of Gem-Ver over to them – split into two groups aboard the two Filipino fishing boats. The men of Gem-Ver left their dog with the Vietnamese.

On June 12, Philippine Independence Day, M2M arrived in Recto Bank. By then, Wilson said the air around Gem-Ver had reeked of rotten fish already floating with the debris. The boat’s owner wept upon seeing his distressed men and his broken boat. He asked for only one thing: that whatever happens, they should try to bring home Gem-Ver, even if in pieces.

One nail at a time for half a day, the men tried to put Gem-Ver together under itchy waters where the dead fish further fermented. By 1 pm, they were ready to bring themselves – and whatever was left of Gem-Ver – home.

A few hours later, the world was told of what had befallen them. In an angry statement to media, Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana blasted the “cowardly action” of the Chinese vessel for “abandoning” the Filipinos.

The Philippine Navy deployed its most capable warship, BRP Ramon Alcaraz, to fetch the fishermen from M2M, where they were fed and clothed once more and asked about what happened. Then they were brought to the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, which received them in a ceremony before sunset on June 14. By then, the fishermen had been at sea for 5 days after their boat sank.

Now swarmed by journalists, they hopped to a smaller grey ship, BRP Tausug, that finally brought them to the shores of San Jose in the evening of June 14.

They were finally home. Safe. Their misadventure was over. Or so they thought. (To be concluded.) – Rappler.com

Conclusion | Despite Duterte, Gem-Ver fishermen buckle down to work

Profiles | IN THEIR OWN WORDS: The fishermen of Gem-Ver

Video | Gem-Ver fishermen eager to sail again

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.